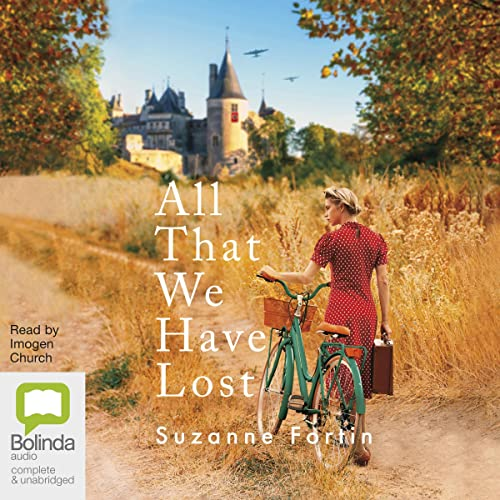

Papa always told us that to be brave doesn’t mean you have no fear.

All That We Have Lost – Suzanne Fortin

It just means you can move forwards in spite of that fear.

In 2019 a beautiful abandoned château is discovered by Imogen Wren. When Imogen husband died, she realised their dream of moving to France would now be on her own. As she starts to rebuild her life among its ruins. Imogen notices that the locals won’t come near the chateau. A dark web of secrets surrounds the house, and it all seems to centre on the war…

In 1944. Simone Varon’s life has been turned upside-down. German troops have moved into the village and she is desperate to avoid them. Until one soldier acts and behaves differently and it is challenging to see him as gentleman vs seeing the enemy of France. Then the Resistance comes calling, the chateau becomes the backdrop to drama between love and duty and devastating consequences that will echo through the decades.

This stunning and terrible dual timeline tale, which was published in October 2021, takes place between the occupied France of World War Two and the war-ravaged chateau of 2019. The topic of the novel’s past and present tales is love and loss. I believe the local pub would be instantly recognisable due to the excellent backdrop and description of Trédion in rural Brittany, which creates a strong feeling of place and time. My gut hurts from the struggle Simone has with Oberleutnant Becker, and I also hate Gossman as much as she does. Unfortunately, Imogen’s current story still deals with the fallout from being perceived as a collaborator when involved in the French resistance.

I kept turning the page as the plot gradually developed and finally revealed the truth. Although I don’t usually choose romance, this dual timeline romance with a dash of mystery is definitely worth reading.