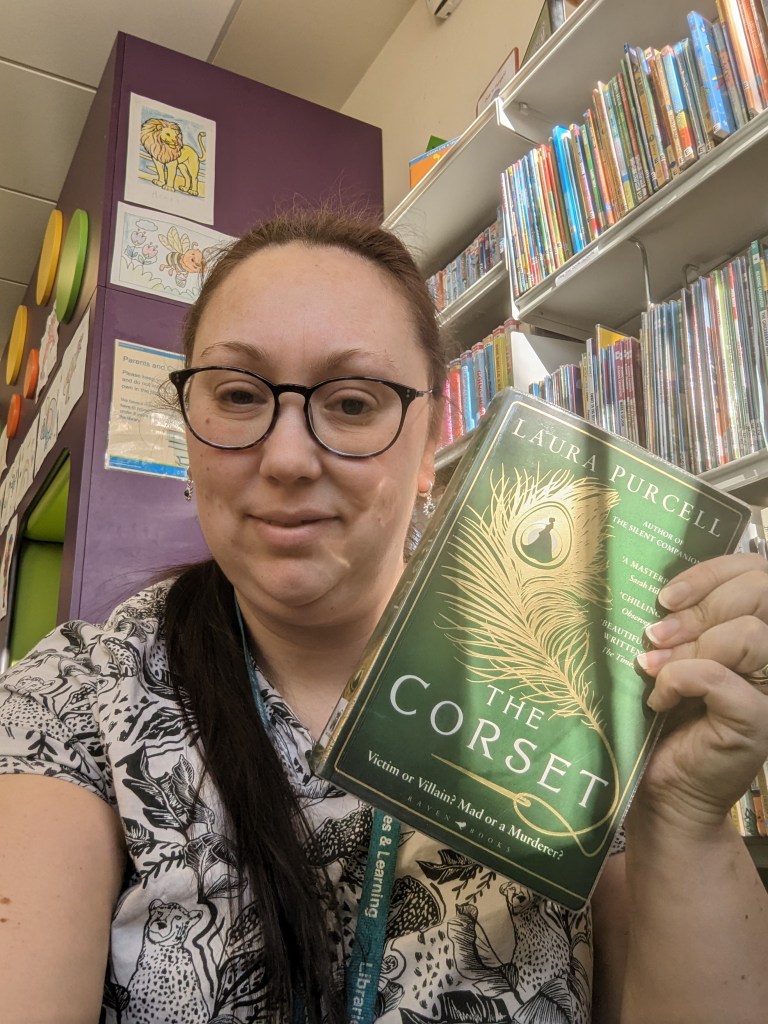

Lindsay Fitzharris with her copy at the UK Launch. Old Operating Theatre in central London. May 25 2022.

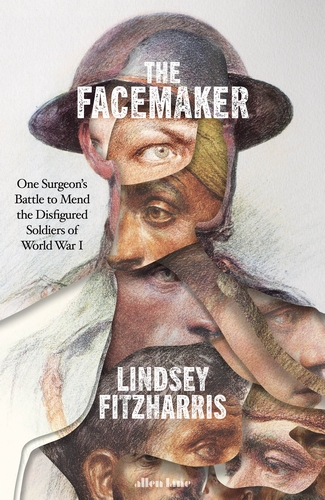

A gentleman walked into the library at Stourport and handed this book directly to a college and me on the staff pod. He had taken The Facemaker off our newly arrived titles less than two weeks ago, and now he had to make sure someone else would read this amazing tribute. He was blownaway by its detail and clarity. I accepted the challenge and i’m so glad I did.

Seraphim Bryant, March 2023

Sera with Stourport’s copy of The Facemaker.

“In France, they were called les gueules cassées (the broken faces), while in Germany they were commonly described as das Gesichts entstellten (twisted faces) or Menschen ohne Gesicht (men without faces). In Britain, they were known simply as the “Loneliest of Tommies”—the most tragic of all war victims—strangers even to themselves.”

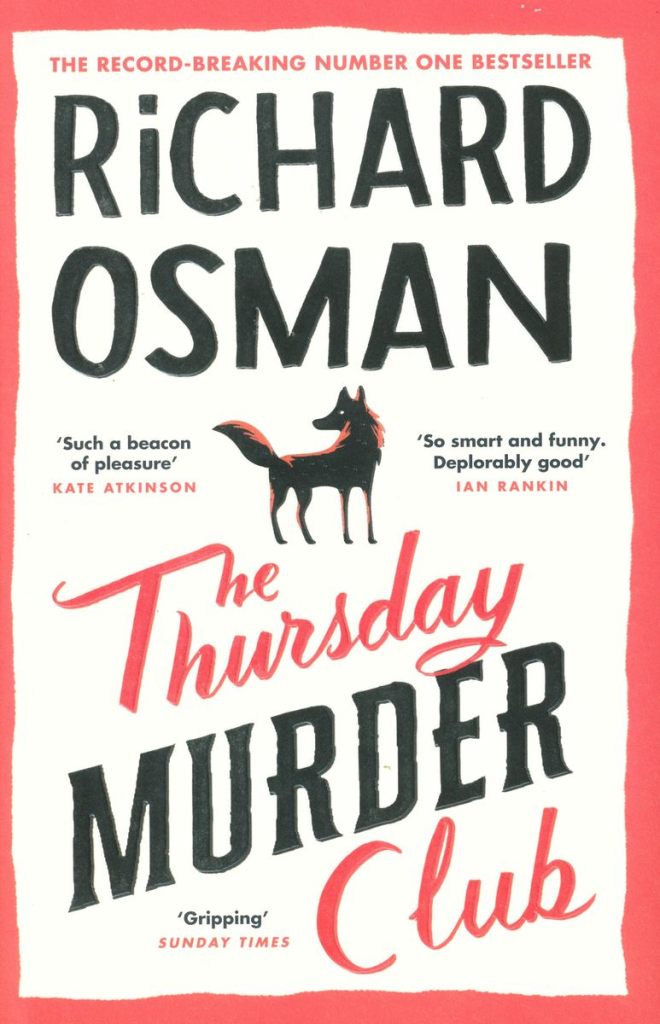

The Facemaker

My Review

Fitzharris is a medical historian but also a truly accomplished writer. There is a lot of information and facts in this book, but thankfully, Fitzharris knows the strength of a well-told narrative. Hardcore History readers’ comments say that the additional WW1 history is distracting in a book focused on such a narrow subject. [Not as narrow as you might think] The accomplishments and the pioneering techniques made during that time in surgery are not just talked about but shown against the staggering advancements in warfare. “The science of healing stood baffled before the science of destroying.” These are not the only comparisons made, nor are doctors from other nations ignored for their efforts, influences and inspirations. Dentistry is shown in a new light, as we now have so much access to dental hygiene we forget how new the treatment is. More than just WW1, history plays a part in how this is miraculous and complicated. Fitzharris also goes on to tell us how plastic surgery went on to become so much more, but also, its partner, cosmetic surgery, grew out of need. Fantastic quotes from varied sources help to solidify the evidence. Yet, the best part of this book is hearing first-hand from soldiers’ accounts and their lives during and after treatment. For me, the closeness to the living subjects was the most brilliant read. The injured had so much to deal with; for those who survived, the chances of being welcomed back into society were slender. How Gillies did more than just treat a man’s injury but also his whole person. The importance of personal care that he instilled in his team, including the nurses, cleaners and artists, is a true testament to the greatness of this doctor. We can easily forget what we are handling when we talk and work with other people. The uniqueness and personality of a man or woman is that personal expression of self; it’s extremely valuable to us and society. So much of what we communicate is not verbal but in the way we move or look at each other.

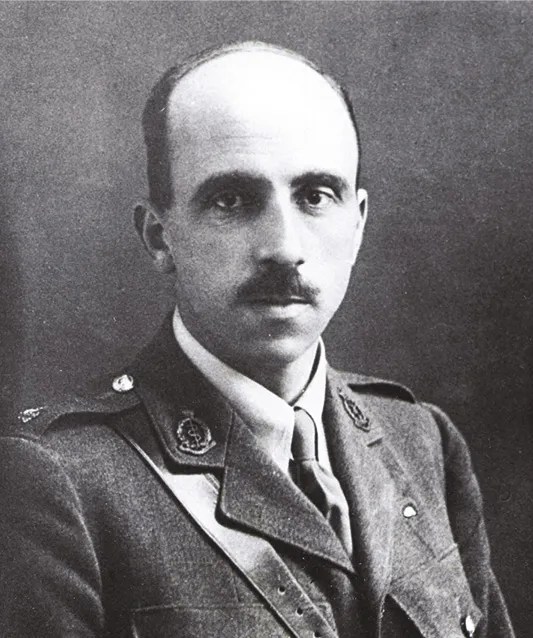

Harold Gillies was an ENT (ear, nose and throat) surgeon, and he volunteered to go over with the British Red Cross when the war broke out. He was introduced to facial reconstruction on the western front by a really amazing character called Charles Valadier. He was a French-American dentist who retrofitted his Rolls Royce with a dental chair and drove it to the show under a hail of bullets; I mean, he was an absolute legend.

So Gillies went back to Britain and petitioned to open his own speciality facial reconstruction unit at the Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot, and that’s how it all began. Eventually, he was so overwhelmed by the number of men needing his help that in 1917 he opened the Queen’s Hospital, which later became Queen Mary’s Hospital, in Sidcup – a hospital dedicated to facial reconstruction.

This was when losing a limb made you a hero, but losing face made you a monster to a society that was primarily intolerant to facial differences. Whereas a prosthetic limb doesn’t necessarily need to look like the arm or leg it’s replacing, a face is an entirely different matter.

The masks were non-surgical solutions created by artists like the sculptor Anna Coleman Ladd, who worked out of a studio in Paris. Sidcup hospital also had a mask-making studio. These masks were all unique pieces of one-off art. When you look at them, it seems almost like a human face. But you have to remember that they are still unmovable. If you were sitting in front of someone wearing one of these masks, it could be a bit unsettling because the masks were expressionless; they couldn’t operate like a face. They were also very uncomfortable to wear, fragile, and didn’t age with the patient. So long term, they weren’t really a solution. Gillies hated them because the masks reminded him of the limitations of what he was doing surgically. However, he sometimes advised recovering patients that they might want to wear masks to go out into society and not be stared at. Time was tricky; it could take more than a decade to rebuild a soldier’s face.

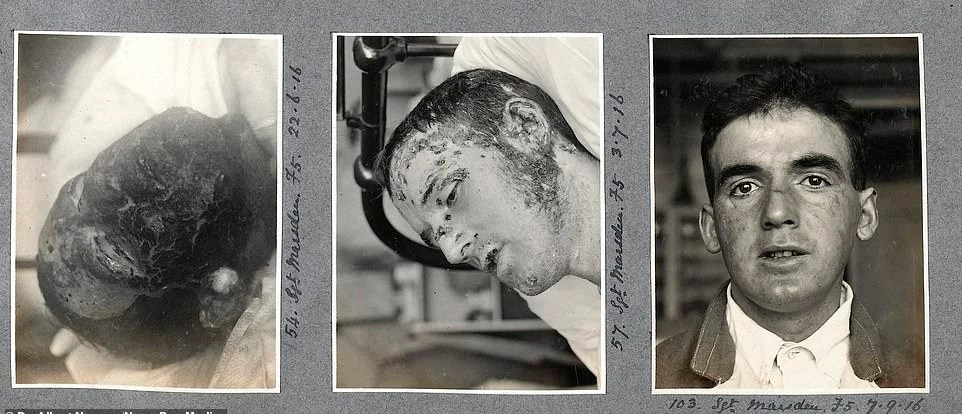

Above: Sergeant Marsden suffered burns to his face and hands after a shell blast. His skin was left entirely blackened by the heat of the explosion. But these photographs, taken between June 22, 1916, and September 7, 1916, show the speed of his face’s complete recovery.

Some Flash Facts Facing Facial Reconstruction Surgery (Plastic Surgery) in History.

- The term “plastic surgery” was coined in 1798. At that time, plastic meant something you could mould and shape – in this instance, a patient’s skin or soft tissue.

- Rhinoplasty [reconstructing the nose] is one of the oldest surgical procedures on record, dating back to around 600 BC.

- Disfigurement has been strongly associated with shame because of its association with disease. Syphilis, which ravaged much of the world for centuries, caused “saddle nose”, where the nose would cave in. People associated syphilis – and the disfigurement it caused – with a moral failing.

- During World War I, patients with facial injuries had to sit on unique benches painted blue when they went out so that people knew not to look at them.

- During the Napoleonic War, there was a widespread practice of comrades killing any facially disfigured battle mates, “mercy killings”, to save them from later shame or ostracism.